Almost every woman in India has experienced sexual harassment in crowded public spaces, such as when someone touched her bottom, pinched or fondled her breasts, elbowed or rubbed against her.

As college students commuting in the overcrowding buses and trams in the eastern city of Kolkata decades ago, my friends and I used our umbrellas to fight back against their predators.

Additionally, many of us scratched stray hands with our long, sharp nails; Others retaliated against men who would take advantage of the crowd to press their penises into our backs with the pointed heels of their stilettos.

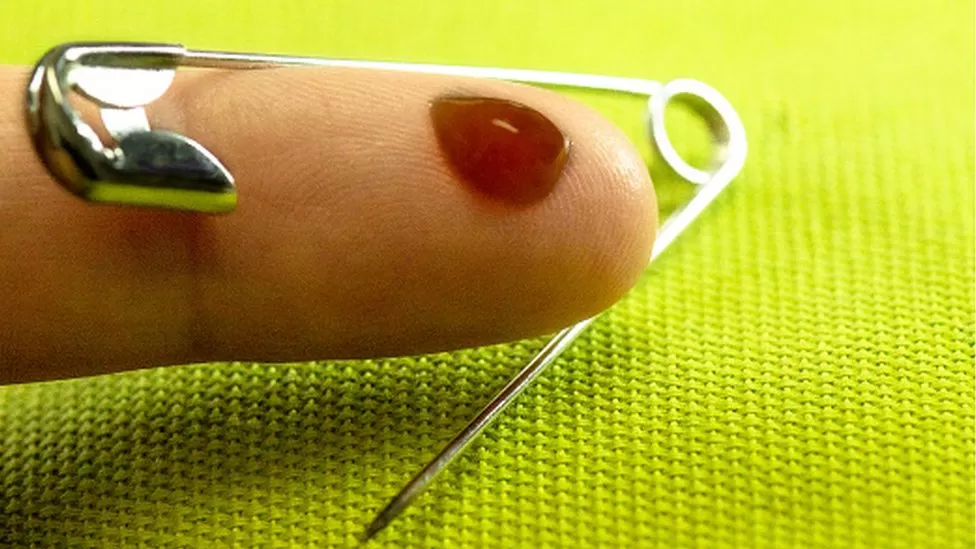

The ubiquitous safety pin served as a much more efficient tool for many others.

Safety pins have been used by women all over the world ever since they were invented in 1849 to hold various pieces of clothing together or deal with a sudden wardrobe malfunction.

Additionally, women all over the world have made use of them to retaliate against their harassers and even to draw blood.

A number of women in India recently confessed on Twitter that they always carried a pin in their handbags or on their person and used it as a weapon to fight perverts in crowded areas.

Deepika Shergill, one of them, wrote about a time when she actually used it to draw blood. Ms. Shergill told the BBC that it happened on a bus she usually took to get to the office. Although the event occurred decades ago, she still recalled the tiniest details.

She was around 20 years old, and her abuser was in his mid-40s. He always carried a rectangular leather bag and wore a grey safari, which is a type of two-piece Indian suit popular with government workers. He also wore open-toed sandals.

When the driver applied the brakes, “he would always come and stand next to me, lean over, rub his groin in my back, and fall over me.”

Back then, she says she was “extremely shy and didn’t have any desire to cause to notice myself”, so she languished peacefully over months.

However, she decided enough was enough one evening when he “began masturbating and ejaculated on my shoulder.”

Five charts show a rise in the number of crimes committed against Indian women. I washed for a very long time when I got home. She stated, “I even withheld telling my mother what had transpired with me.”

“That night, I couldn’t sleep and even considered quitting my job, but then I started thinking about getting what I deserved. I wanted to hurt him physically to prevent him from ever doing this to me again.

Ms. Shergill boarded the bus the following day wearing stiletto heels and carrying a safety pin.

“I got up from my seat and crushed his toes with my heels as soon as he came and stood next to me. I was overjoyed when I heard him gasp for air. After that, I punctured his forearm with the pin and quickly got out of the bus.”

She claimed that was the last time she saw him, despite the fact that she continued to take that bus for an additional year.

The story of Ms. Shergill is shocking but not uncommon.

On an overnight bus traveling between the southern cities of Cochin and Bengaluru (Bangalore), a colleague in her 30s described an incident in which a man repeatedly attempted to grope her.

She stated, “I initially shook him off, thinking it was accidental.”

She realized, however, that it was deliberate and that the safety pin she had used to secure her scarf “saved the day” when he continued.

I poked him, and he withdrew, but he kept trying, and I kept trying to poke him back. He eventually withdrew. “I feel silly that I didn’t turn around and slap him, but I’m happy that I had the safety pin,” she says.

She continues, “However, when I was younger, I was wary that people wouldn’t support me if I raised an alarm.”

Activists contend that the majority of women’s feelings of shame and fear encourage molesters and contribute to the problem’s widespread nature.

56% of women in 140 Indian cities in 2021 reported being sexually harassed on public transportation, but only 2% reported it to the police, according to an online survey. The vast majority of respondents stated that they either took action on their own or that they chose to ignore the situation, frequently emigrating out of fear of making a scene or worsening the situation.

“Feelings of insecurity” were cited as the reason by more than 52% of respondents for declining educational opportunities and job opportunities.

“Fear of sexual violence impacts women’s psyche and mobility more than the actual violence,” asserts Kalpana Viswanath, co-founder of Safetipin, a social organization that strives to make public spaces safer and more welcoming for women.

“We are denied equal citizenship with men when women start imposing restrictions on themselves. It has a much greater impact on women’s lives than molestation itself.”

Ms. Viswanath emphasizes that harassment of women is a global problem as well as a problem in India. “Transport networks were magnets for sexual predators who used rush-hour crushes to hide behavior and as an excuse if caught,” according to a survey conducted by the Thomson Reuters Foundation among 1,000 women in Cairo, Mexico City, Tokyo, London, and New York.

Ms. Viswanath claims that African and Latin American women have informed her that they also carry safety pins. Furthermore, the Smithsonian Magazine reports that in the US, ladies utilized hatpins even during the 1900s to wound men who became really close.

India, on the other hand, does not appear to recognize public harassment as a significant issue, despite topping several global surveys on its prevalence.

According to Ms. Viswanath, this is partially due to the influence of popular cinema, which teaches us that harassment is just a way of wooing women, as well as poor reporting, which prevents it from being included in crime statistics.

However, Ms. Viswanath claims that conditions have improved in a number of cities over the past few years.

Buses in Delhi’s capital have panic buttons and CCTV cameras, training sessions have been held to train drivers and conductors to be more responsive to female passengers, and marshals have been added to buses. Women can also get help by calling apps and helpline numbers provided by the police.

According to in any case, Ms Viswanath, it isn’t generally an issue of policing.

“I think the most important solution is that we talk more about the problem; there needs to be a coordinated media campaign that teaches people what is acceptable behavior and what is not,” says the author.

Ms. Shergill, my colleague, and millions of Indian women will have to keep their safety pins handy until that happens.